200 mm Prime Lens Tutorial (Part C): Comparison with the Cooke Triplet

1. Prime lens vs Cooke Triplet

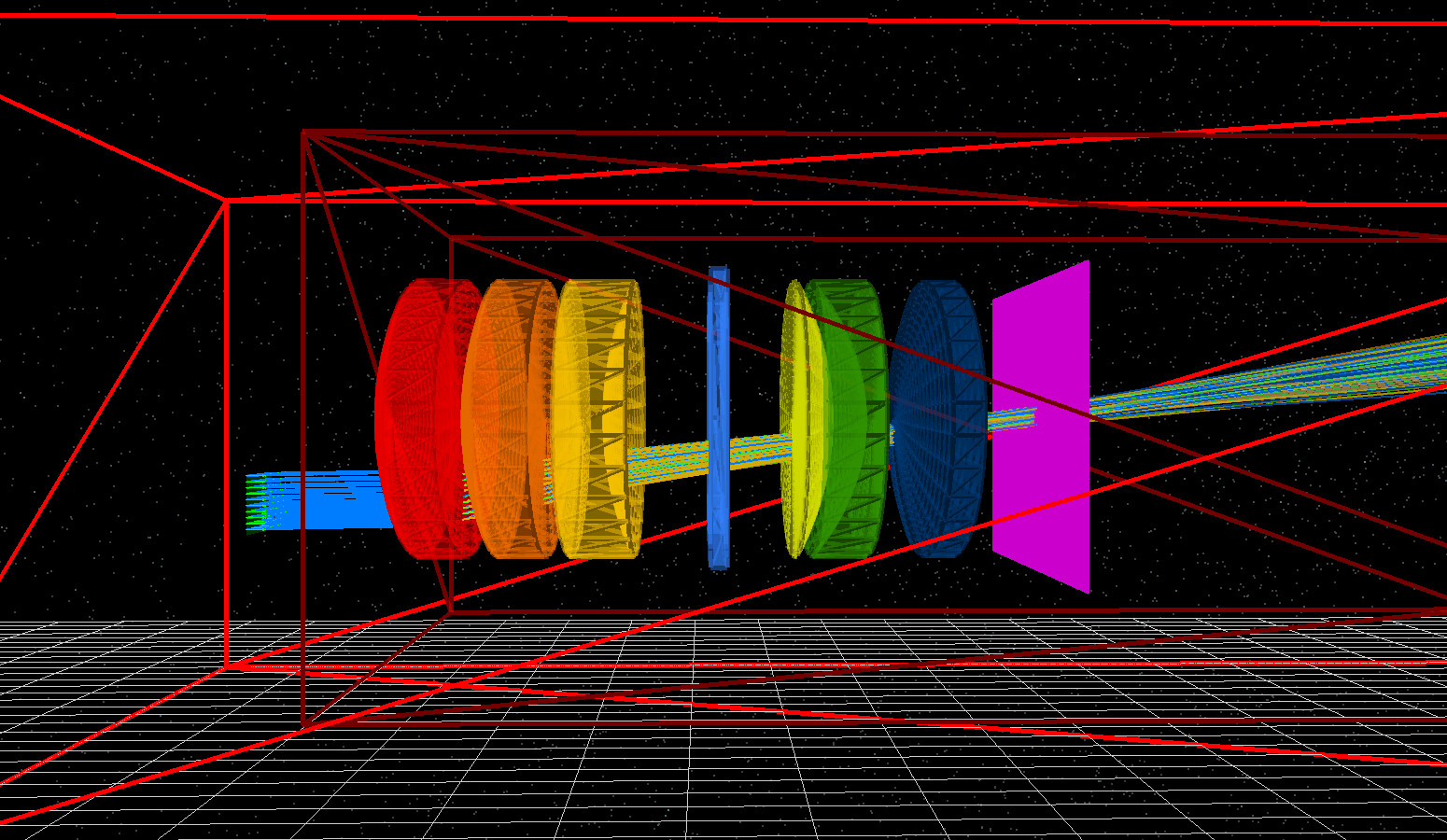

If you have not already worked through the Cooke Triplet tutorial, it is worth doing so before continuing. The Cooke Triplet (??). is one of the most fundamental and historically important lens designs, and it provides a clear reference for how classical optical systems were constructed and balanced. When you repeat the same ray-based workflow on the Cooke Triplet, important differences in ray behaviour become immediately apparent. Although both systems form images, they represent very different design philosophies: in the Cooke Triplet, optical power is concentrated into a small number of elements, leading to abrupt, strongly localised ray bending and rapid divergence of marginal rays from paraxial ones. This makes the Cooke Triplet ideal for visualising classical aberration balancing, while also making its limitations easy to see.

2. Distributed optical power and the role of the stop

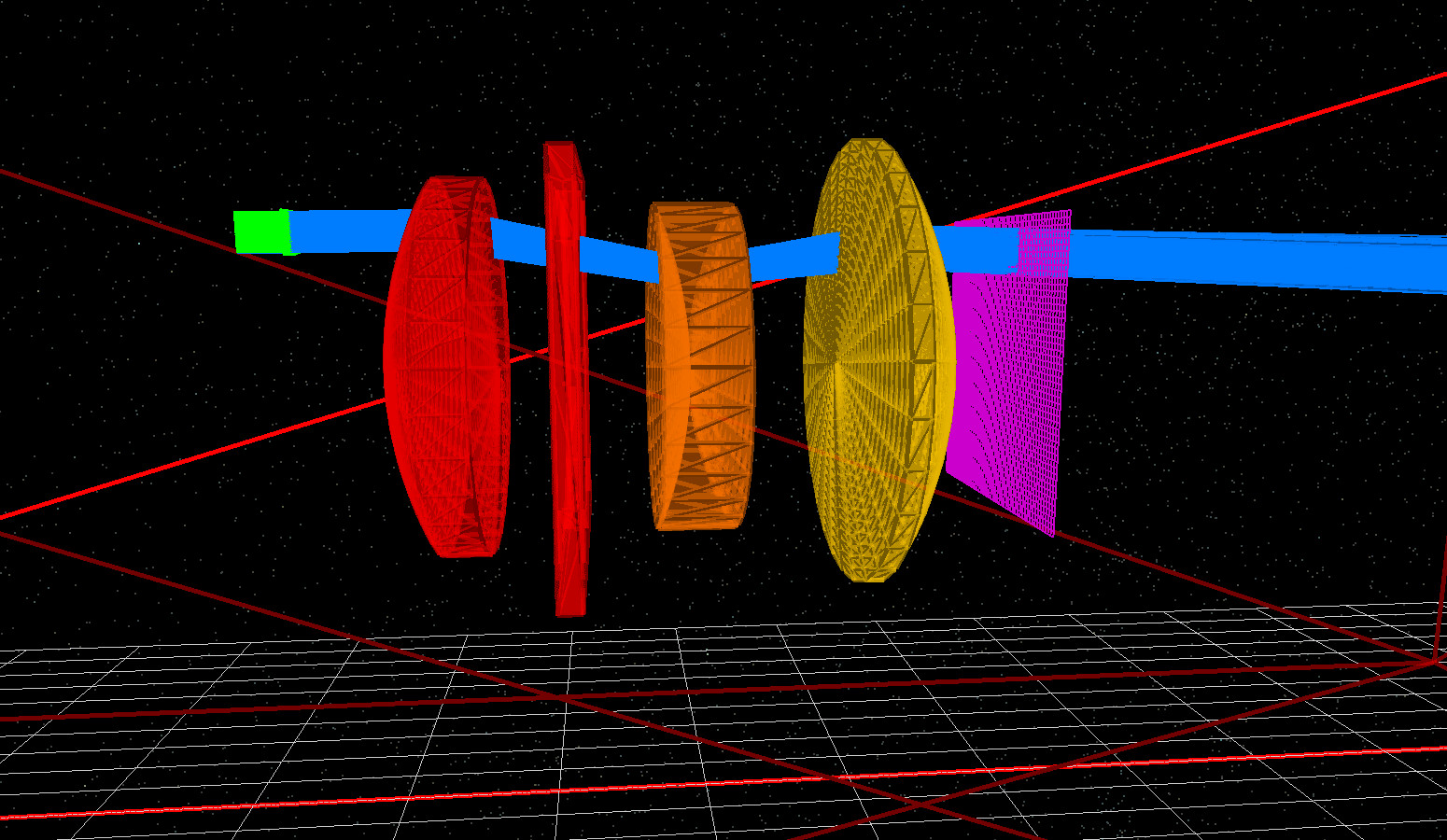

In contrast, the modern 200 mm prime lens (??) distributes optical power across many more surfaces. Individual refractions are gentler, and rays are steered gradually rather than redirected abruptly; no single surface appears to “do all the work”. Although the lens is more complex, the ray paths typically look calmer and more organised. This is a characteristic feature of modern photographic optics: complexity is used to control ray families, not simply to increase raw power.

The aperture stop also plays a different role. In a Cooke triplet, the stop is usually close to the optical centre, and stopping down mainly reduces the overall cone of rays in a symmetric way. In the modern prime, the stop is often optically displaced, and rays are intentionally shaped both before and after it. As a result, changing the stop can alter which surfaces are illuminated and where clipping occurs, sometimes far from the stop itself.

3. Chief and marginal rays: field dependence and aberrations

Chief-ray behaviour highlights another key difference. In the Cooke triplet, off-axis chief rays tilt strongly as field angle increases, making field curvature and coma visually obvious. In the modern prime, chief rays are more tightly controlled and often approach the detector at smaller angles. Field dependence is absorbed gradually rather than expressed as a single dominant tilt, helping modern lenses maintain image quality across a wider field.

Marginal rays are treated very differently as well. In the Cooke triplet, marginal rays strike the strongest curvatures and are responsible for most aberrations. In the modern prime, marginal rays are guided through dedicated zones of the optics, often passing through paired positive and negative elements designed specifically to manage them. Visually, marginal rays in the triplet appear “wild”, whereas in the modern lens they appear controlled and constrained.

4. Design evolution and robustness

Sensitivity to perturbations also differs markedly. Small changes in detector position, stop size, or field angle tend to produce large and obvious effects in the Cooke triplet. The modern prime responds more gently: the same perturbations lead to subtler changes in ray structure and footprint shape. This reduced sensitivity reflects the use of additional degrees of freedom to stabilise performance.

Seen side by side, these two systems illustrate the evolution from minimal-element designs, where aberrations are balanced carefully but exposed, to modern multi-element lenses, where ray behaviour is actively managed throughout the system. Being able to see this difference directly in ray paths is one of the strengths of a geometry-first ray-tracing workflow.

What you can now do (Part C)

- Compare lens design philosophies by eye by inspecting how rays propagate through a classic Cooke Triplet versus a modern multi-element prime.

- Recognise where optical power lives: concentrated into a few dominant surfaces in the Cooke Triplet, versus distributed gently across many elements in the modern prime.

- Interpret chief- and marginal-ray behaviour as a direct visual consequence of design choices, not just as abstract aberration terms.

- Understand the changing role of the aperture stop and why altering it can affect ray paths and clipping far from the stop itself in modern lenses.

- Visually assess robustness by observing how sensitive each system is to small changes in field angle, stop size, or detector position.

Big picture takeaway

- Simple lenses expose aberrations clearly; modern lenses manage them actively.

- More elements do not mean more chaos — they provide more control.

- Ray paths themselves tell you why a design behaves the way it does.

- Being able to “read” a lens by eye is a powerful complement to any metric-based analysis.